Today I gave a tutorial to a hapless bunch of medical students. Sweet, innocent, trusting kids who just want to be good doctors and there I was giving them a rubbish tut. If I were their parents or the NSFAS or whoever is funding them, I might demand my money back. The tut was on brain tumours, the second most common cancer type in children and the most badly recognised and treated.

To be fair to myself, this is not an easy topic to cover and I guess that is why it is not well taught. I recall that Neuroanatomy was possibly my worst subject ever (apart from Physics and Chemistry. Oh, and Family Medicine) inducing equal parts apathy, despair and panic.When trying to learn Neuroanatomy I panicked, leading to despair, culminating in apathy. Eventually all I could recall of the subject was the nasty feelings, and very little anatomy. Neuroanatomy seemed to exist at the intersection of these three feelings.

Thankfully, I seem to have picked up a fair amount over the years and now it all makes a lot more sense. But to make things a bit more complicated, the classifications of brain tumours keep changing as research into the molecular make-up of these tumours grows exponentially. The new WHO classification of brain tumours bears almost no resemblance to what I remember from Med School, or registrar time.

We used to talk about benign versus malignant brain tumours. Parents ask us with hope and fear in their voices, “Is it benign, doctor?” Pah! Who came up with that terminology?

Imagine a big, floppy Saint Bernard lolloping through the snow, the wind blowing its silly ears back, its great paws digging adorable plate-sized holes out of the white stuff. It’s kinda gorgeous.

Now imagine that same slobbery, over-sized mutt barging around in your precious one roomed flat, the first accommodation you’ve ever paid for yourself. It has one bedroom big enough to fit your three-quarter size bed, a galley kitchen , a lounge filled with one sofa and armchair and your desk. The bathroom is just big enough for the shower, the toilet, one towel and a stick of deodorant.

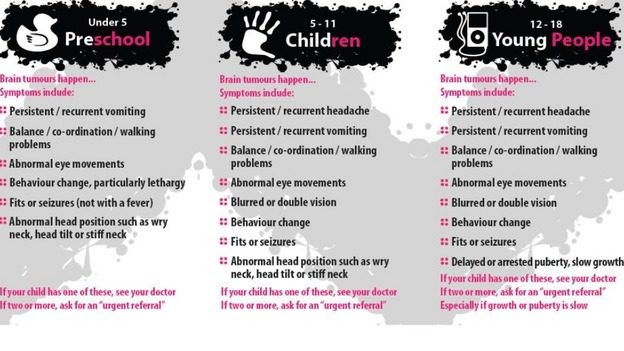

The dog in the snow is benign, the dog inside your precious apartment is definitely malignant. There’s no way it can do anything but cause harm. And so it is with brain tumours. No matter whether they grow slowly or fast, whether they look benign or malignant under the microscope, they always cause serious damage. The skull is a closed system, designed to protect the fragile, essential contents, not accommodate a great big intruder. Brain tumours cause damage to the developing brain and affect growth, hormone release, cognition, emotions and movement. Kids with brain tumours can have such a wide variety of symptoms it’s no wonder they are so commonly misdiagnosed.

So, my apologies to the med students and I promise I will make a lovely handout that makes it all much clearer. I’m also going to talk formally with my colleagues to make sure we all teach this topic better and more frequently.

This is how research can inform practice, how we can use something we’ve learned that has gone through an ethics committee and peer review to teach better, and hopefully to get more kids to the right specialised services much quicker. The more children reach us in the earlier stages, the less likely it is that they will experience the devastating side effects of these tumours if they can be treated correctly.