This last week I have been training hard, hoping against hope (where did that expression come from?) that all this effort will pay off. I need all the inspiration I can get, as I am still not feeling that this lark is possible. I have my beautiful TomTom watch, obtained for free using points gained over the years from my gourmet bank. Most expensive watch I’ve ever owned and I would never have bought it if I didn’t have the points. Suggestion courtesy of my better half, of course. It records my heart rate, cycle route, exercise duration and more. It calculates calories expended and buzzes when my heart rate is too high or not high enough.

I’m on Strava, which maps my cycling endeavours and then compares them to other people – don’t like that part. Friends who “follow” me can send me kudos, and shallow me, I love it.

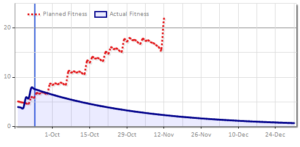

Now I’ve joined Fittracker to get a plan for the next six weeks. This super website is both encouraging and terrifying. Just look at this graph:

It looks like if I carry on at this pace I might just hit the target, but look how far I have to go. I’m certainly feeling ever so slightly more muscular, the scale shows a decrease of 2.5 kilos since I got back from the best holiday ever, three weeks ago – Mauritius baby! – and my trainer thinks I am already improving. But oh brother! Look how far I have to go. The baseline was pretty low, I admit, but seeing it like this is a wake-up call of note.

I have to avoid injury – my darling friend and unofficial Coach keeps reminding me that cardiovascular fitness improves faster than muscular (or something) so I have to be careful, at my advanced age, not to injure myself. I learned today (sitting Googling on the couch, too tired to move after a mammoth training session this morning) that hard training sessions depress the immune system, making us more susceptible to passing bugs. That explains why I always always get sick just when I’ve started getting into a hectic exercise rhythm. So now I’m dosing myself with daily zinc and vitamin C, the only things vaguely shown to boost the immune system.

We have a saying in the medical field – “If it’s not documented, it’s not done”. It doesn’t matter if you saved three lives last night, if you didn’t write it down, it never happened. Put another way – you can’t defend yourself against accusations of negligence if you didn’t document that you did the right thing. And in the big picture, if you haven’t published your research, it may well have never happened and more importantly, you’ve let down all those patients who on some level expect you to make some sense of their diseases.

We don’t “document” enough in this country – clinicians are so busy seeing patients, dealing with admin, teaching students etc that they don’t find or make the time to research. And if they manage to do a bit of research, they don’t have time to write it up and publish it so other people can benefit from it. The statistics on childhood cancer in South Africa are so limited and dated, all because clinician-scientists like me don’t have the time or the research support to contribute to the research literature. We cure kids, but if it’s not documented, it’s not done. We think we know how many overall, but it’s an educated guess at best until it’s gone through a formal ethics, review, research process and peer-review. We need to document the incidence rate (how many kids are diagnosed with cancer) and the mortality rate (how many die) to set a baseline so we can build on that.

A child who gets cancer in the U.K., say, has an approximately 80% chance of being cured. 80% sounds good, you may think, but imagine the terror of the parent, and the child who may grasp that awful possibility, of being in the 20%. Now imagine being in a low or middle income country, and being given the odds of 50% survival. That’s right, kids here have a even chance of living or dying if they’re diagnosed with cancer. That’s my educated guess, and until someone publishes something that says different, I’m sticking with it.

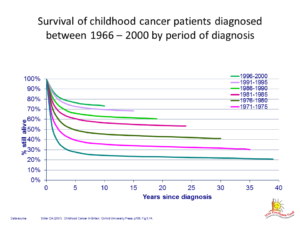

This (fuzzy) graph shows long-term survival rates of kids with cancer in high income countries. Over the decades, survival rates have risen higher and higher, due to a number of factors which include solid research, improved supportive care and new drugs and new combinations of old drugs. South Africa, however, is still sitting round 50%, the same level seen fifty years ago!

Now we know where we have to go, folks. Research will tell us why our survival rate is so low and how we can make it better. Our baseline is 50% – let’s raise it together.

(Please forgive the fuzzy pics – I’ll figure out how to make them look sparkly and fresh sometime soon, promise. )